-

Mapping Peer Support Futures

On February 27, I facilitated a workshop for PeerWorks members with the goal of mapping the future of mental health peer support and outlining possible scenarios. This workshop was attended by 6 peer workers, primarily from Ontario. Below is a summary of some of our discussions.

[A short summary of the results from this workshop is also available on the PeerWorks blog.]

Mapping the Future

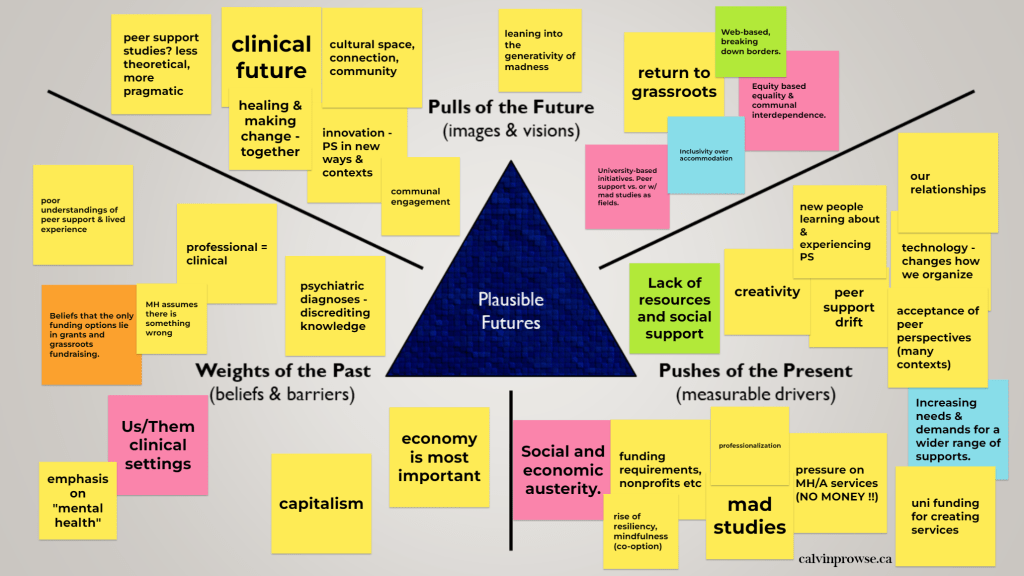

We began by mapping our perspectives on the future of peer support, using a tool called the Futures Triangle developed by Sohail Inayatullah (2008, 2013, 2023). This tool allowed us to explore the tensions between the pulls of the future, pushes of the present, and barriers of the past. Considering the interplay between these forces allows us to generate plausible scenarios of the future around current uncertainties.

[A short mini-zine summarizing the content of the mapping exercise is available through my online shop, both as a free digital download or for purchase in physical form]

Pulls of the Future

What visions of the future are we being drawn toward?

The Clinical Future

In the clinical future, peer support continues on its current trajectory of integration within clinical healthcare systems. The history and unique benefits of peer-led organizations are lost as they become absorbed into mainstream services. In order to gain legitimacy within mainstream systems, peer support adopts the frameworks of clinical providers, leading to increased peer support drift.

Back to Grassroots

In this future, peer support returns to a more grassroots context, primarily taking place within autonomous peer-led organizations such as Consumer/Survivor Initiatives (CSIs) or independent grassroots initiatives. This future is characterized by an emphasis on values such as equality, equity, inclusivity, collectivity, interdependence, and social justice. Peer support is merely one component of a larger peer culture, serving as one of many entry points into peer community. Experiences of “madness” are understood as potentially meaningful experiences which can also serve as the foundation for social change efforts. Creativity and the arts may play a larger role in this future.

The Innovative Future

This future is characterized by innovation, mobilizing peer support in new ways and in new contexts. Technology is embraced as a tool for connection, leading to peer support increasingly taking place online and in digital communities. Peer support becomes an integral part of post-secondary education systems, with new avenues emerging for students to engage in mutual support. “Peer Support Studies” emerges as a new academic discipline, as a more pragmatic complement to its cousin Mad studies; instead of dense academic theory, Peer Support Studies emphasizes plain language perspectives and theory developed through lived experience.

Pushes of the Present

What trends in the present are pushing us toward the realization of particular futures?

Climate of Austerity

Decades of social and economic austerity has resulted in increased social need paired with a lack of economic resources and social support. This has led to significant strains on the mental health and addictions system more generally, as well as the peer support sector in particular – which has suffered from chronic underfunding for decades. Smaller organizations like CSIs are unable to compete with larger clinical organizations for the limited number of funding opportunities available, due to limited staff resources and the high amount of labour necessary to apply for short-term grants on an ongoing basis.

Peer Inclusion

Peer perspectives are increasingly recognized for their value and actively sought out – both within and beyond the mental health & addictions sector. Several post-secondary schools have developed peer programs or roles to support the student population. As youth experience peer support for themselves, a new generation of peer supporters is entering the sector with fresh perspectives.

Professionalization, Peer Support Drift, & Co-option

The other side of inclusion is co-option – when “inclusion” goes wrong. Concepts emerging from both within and beyond the consumer/survivor movement (e.g. recovery, mindfulness, resiliency) are increasingly adopted by mainstream systems – often in ways that do not maintain integrity with their roots. Likewise, there are concerns that peer support may be co-opted by mainstream systems as a tool to meet clinical goals, leading to the potential for peer support drift. A desire to be seen as credible within the healthcare system has led to an increased emphasis on professionalization within the peer sector, as well as discussions about the benefits and limitations of requirements for formal education.

Technology

Technology continues to change the ways we connect and organize. In earlier decades, the consumer/survivor movement maintained momentum through publishing newsletters and organizing in person meetings, conferences, and protests. The ability to access information from the comfort of our home has made it easier to share information and connect across distance; on the other hand, the anonymity and alienation of the digital world, along with the constant bombardment of “content,” may make us feel more disconnected from each other and less likely to take action. Our personal relationships and ability to organize offline can be one powerful asset for us to continue to draw on, even as we continue to adapt to an increasingly digital world.

Barriers of the Past

What deeply-held beliefs and worldviews are barriers to realizing our preferred futures?

Capitalism

This economic structure prioritizes profit over people, leading to limited funding for health and social services. Deeply entrenched within this system, it becomes difficult to imagine alternative funding structures to grants and government funding. It also prevents us from questioning whether funding itself is in fact necessary for our work; we forget that many early consumer/survivor groups organized successfully with little to no funding.

Clinical Frameworks

Clinical perspectives continue to dominate understandings of mental health and addiction, with a focus on biological illness rather than a holistic understanding of wellness that attends to social, economic, political, and spiritual factors. The dominance of clinical perspectives results in the assumption that being professional means being clinical, perpetuating peer support drift as peer supporters are pressured to adopt clinical approaches in order to demonstrate their legitimacy. The perspectives and knowledges we gain through lived experience are often discredited because of assumptions about our capacity for “insight.” Another barrier is the grassroots / clinical divide; the assumption that these two streams of peer work cannot work together in harmony.

Poor Understanding of Peer Support & Lived Experience

Despite decades of organizing and our increased inclusion within mainstream health and social service systems, the unique value of lived experience continues to be misunderstood. As a result, a limited number of people who might benefit from peer support are able to access it. As well, the lack of understanding about the unique value of peer support results in those with decision-making power making decisions about the implementation of peer support that do not maintain integrity with its history and values.

Emerging Issues & Uncertainties

What emerging issues and uncertainties have the potential to dramatically shape the future(s) of peer support?

Funding Structures & Availability

Will peer support see a dramatic increase in funding, or continue to be chronically underfunded – causing peer supporters to leave the field in search of increased financial stability? Or, the alternative – will peer support see a further reduction in funding, or have its funding eliminated entirely? Where will our funding come from: governments, grants, private donors, corporate sponsorships, or the community itself?

Government

What will governments look like in the future – and how might this impact the peer sector, as well as our funding? This might be impacted by the political party in power, as well as changes to the electoral system or our political system more broadly.

Peer Support Drift & Professionalization

Will peer support continue on its current course toward peer support drift, or will we be able to succesfully interrupt it and maintain the integrity of peer support? Will peer supporters become fully recognized as professionals in their own right – and, if so, how? Will we appeal to the expectations of clinical frameworks in the pursuit of legitimacy, or will we be able to redefine professionalism in a way grounded in peer values and culture? Will peer support begin to require post-secondary education – and, if so, how might this impact the value placed on knowledge gained through lived experience? Will a degree in peer support emerge, or a discipline of Peer Support Studies?

Peer Culture

Related to peer support drift is the question of peer culture. Will we be able to re-infuse peer work with a cultural perspective, moving us towards a more holistic approach to culture, community, and collective identity similar to other marginalized groups? What might a peer sector committed to peer arts and culture look like? What role might activism play?

Social Movements

New social movements operating from a peer perspective continue to emerge, as well as new “waves” of previous movements (e.g. harm reduction, neurodiversity). How might these distinct practices of peer support influence the mental health and additions peer sector? Will we be able to successfully cross-pollinate through the mutual exchange of knowledge, thus re-infusing mental health/addictions peer support with fresh perspectives? Will we be able to come together in solidarity, with the awareness that our struggles are deeply connected? Or will we fail to build the coalitions necessary for an intersectional politics of peerness?

Technology

We are living in a period of rapid technological change. As a result of technology such as Zoom, the peer sector was able to rapidly respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and provide accessible supports while mainstream services struggled to adapt. This also enabled peers located further away from organizations to access support from the comfort of their home. We have also seen a rapid rise in the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the world: however, the impact this may have on the peer sector currently remains unclear.

Scenario Planning

How might technology shape the future of peer support? What role might it play within these futures?

We broke into groups to develop two scenarios exploring this question. Scenarios allow us to anticipate what challenges and opportunities may arise in the future, so that we may better respond to them.

➀ Integrated Tech: “Online Peer Revolution”

In this future, peer support and the rise of technology live in harmony. Peer support increasingly moves into the digital world, with peer communities forming through online platforms such as Facebook and Discord – with peer support even taking place through Virtual Reality (VR) platforms!

In this future, connection and support is only a click away. Technology has democratized peer support, making it available to all. Peer support takes place within communities centered around a variety of identities and experiences, not only mental health and addictions. This future counters current trends related to professionalization, returning peer support to a more grassroots, naturally-occurring context. At the same time, an increased amount of peer support is provided by people without any formal training, leading to the possibility for some of the history of mental health peer support to be lost – in this future, peer support drift remains a concern.

➁ No Tech: “Surviving the Machine”

This scenario takes place in a more extreme context. Following the technological singularity in 2030, a war breaks out between humans and machines. Formal education systems crumble as priorities shift to survival; instead, knowledge is passed down from elders within the community.

The war ends when an electromagnetic pulse from the sun wipes out all machines, leaving the remaining survivors to rebuild. The world is healing from collective and individual trauma, and peer support steps up to fill the gap. Without technology to connect across distance, the world becomes fractured into small independent communities led by community councils.

These communities are deeply mistrustful of technology. However, a small faction emerges advocating for the use of technology in limited amounts – primarily within the younger generation that was born after the war.

This future is characterized by a broader worldview of community care which emphasizes the necessity of mutual aid for everyday survival. At the same time, limited communication has made building trust outside the community more challenging, and a scarcity of resources has made many communities weary of outsiders. On the other hand, some communities may view outsiders not as a threat, but as an opportunity: a way to share stories and learn more about the outside world.

Discussion

These scenarios raise significant questions and considerations both within the peer sector as well as the broader world:

- Will technology be a tool for connection, or a threat to everyday life?

- What might the peer sector look like if we return to a world without technology?

- How can we ensure that knowledge is passed down to the next generation of peer supporters?

- How might we foster futures grounded in interdependence; where peer support, community care, and mutual aid are understood as integral to our survival and way of life?

These scenarios paint two very different pictures of the role that peer support may play in the future; at the same time, they also share similarities. In both scenarios, peer support returns to a more grassroots, naturally-occurring context, led by lay people: providing support not only around mental health and addictions, but also identity, culture, and everyday life.

References

Sohail Inayatullah (2008). Six pillars: Futures thinking for transforming. foresight, 10(1), 4-21. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680810855991

*Sohail Inayatullah (2013). Futures studies: Theories and methods. In There’s a Future: Visions for a Better World (pp. 37–65). BBVA. https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/books/there-is-a-future-visions-for-a-better-world/

*Sohail Inayatullah (2023). The Futures Triangle: Origins and Iterations. World Futures Review, 15(2-4), 112-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/19467567231203162

*open access

-

Peer Support Futures: Conference Presentation

On February 6, I will be doing a presentation on my research on peer support futures as a part of the 4th annual virtual Peer Support Strong conference, hosted by PeerWorks and the Lived Experience & Recovery Network.

Introducing Peer Support Futures:

On Hope, Dream, and Building UtopiaTuesday, February 6

2:00 – 2:45 Eastern TimeThis presentation is a reading of a paper based on my MA major research paper, Dreaming Peer Support Futures (2023). It will be accompanied by a PowerPoint presentation of key ideas.

In this paper, I explore the field of mental health peer support through the lens of futurity, utopia, and dream(ing). It is an attempt to encourage a futural (re)turn within the sector, while recognizing that dreaming has always been at work and play within peer support theory and practice.

In some ways this paper serves as a portal to the past – back to the field’s roots within the psychiatric consumer/survivor movement, a social movement that emphasized dreaming and crafting alternative futures; alternative ways of understanding and responding to experiences of psychic distress. At the same time, it is also an effort to trouble these same roots and encourage us to imagine futures otherwise.

-

Dreaming Peer Support Futures

My major research paper, Dreaming Peer Support Futures, is now available on YorkSpace!

Drawing on practices of diffractive reading supported by zine-making methods, throughout this major research paper I explore the question: “what could a lens of futurity offer the discipline of consumer/survivor peer support?”

In Chapter 1, I engage in a theoretical dialogue between the realm of peer support and notions of futurity to demonstrate the benefits and alignment of a futural (re)turn within the peer support sector, setting the stage for the rest of my analysis.

In Chapter 2, I explicate the ways – the whys and hows – that peer supporters are exploited by the psychiatric industrial complex under neoliberal rule, grounded in a historical approach that draws on the frameworks of confluence (Joseph, 2015) and neuroliberalism (Moussa, 2019) so that we may “learn from the past” (Butler, 2000, p. 166) in order to better anticipate the future.

In Chapter 3, I explore how the peer support sector is itself implicated in upholding systems of oppression (white supremacy, Western dominance, colonization, and colonialism) by troubling the “peer support origin story” and the current demographics of the field, as well as identifying what futures are currently in construction.

Lastly, in Chapter 4, I explore how we can draw on the lessons of funga and flora to both locate ourselves within the present and dream peer support futures beyond the limits of realism.

-

Dreaming Together: (Re)Imagining Pathways for Peer Advancement

by Colene Allen & Calvin Prowse.

On May 9, 2023, during the PeerWorks Annual Conference, we facilitated a “dreaming together” networking session / workshop on the topic of possible pathways for career advancement within the peer sector. During this workshop, we posed a series of questions to participants to explore and brainstorm through small group discussion. These questions explored current and possible pathways for advancement both within and beyond the peer sector, as well as how our lived experience and peer support can be an asset in other fields.

We each came to develop this workshop based on our own unique backgrounds, perspectives, and wonderings, as well as through a shared concern about the limited opportunities for advancement within the peer field. Colene has drifted in and out of both paid and volunteer peer support roles, as well as roles in other sectors where lived experience and peer support values and skills have been an asset. Calvin’s interest in this topic came from their MA research on peer support futures, as well as their own uncertainty about the next steps of their career within the peer sector. Colene wanted to explore how other roles can function as entry points into peer work, and Calvin wanted to explore possible new roles within the peer field.

This “dreaming together” workshop provided an opportunity for us to explore the current state of the peer sector as well as its possible futures alongside conference attendees… Continue Reading on the PeerWorks Blog

-

Dreaming like Fire Ants

For women … poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

– Audre Lorde, 1977/2007

Poetry is Not a Luxury

in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, p. 37Poetry is not a luxury: it is a way of feeling, of giving our dreams shape; an ancient technology for imagining something radically different than the here and now, buried but never forgotten.

Poetry is not a luxury: it is a matter of survival in a world that demands and depends on the death of our dreams; our ability to imagine something different, something better, something new.

Poetry is hope: it is the promise of alternative futures; poetry is resistance, refusal, and revolution: it is an essential way of being, whose qualities have been obscured in the subjugation of feminized feminist feeling under the (masculine, colonial, white) supremacy of logic and rationalism1,2– a cutting away of the soul.3

I am reminded of fire ants. Fire ants have a stage of sleep called Rapid Antennal Movement (RAM) sleep, which appears to be a rough analogue of Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep in vertebrates such as us.4 The majority of our dreams take place during REM sleep; I wonder: what do fire ants dream of?

Poetry is not a thing, an object, a noun: it is a verb, a doing, a dialogue – between poet, reader, listener, and the worldviews we hold within us, always in a process of (re)becoming. Poetry does not happen in isolation: it demands an audience; it is an invitation toward an entangled mode of relation.

Some species of ants can have multiple queens for one colony; such is the case with the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. In fire ant colonies with more than one queen, their sleep schedules synchronize with one another:4 they move together.

I wonder: how can we synchronize with each other?; how can we dream, together?; how can we move together?; how can we breathe, together; to be(come) co-conspirators for decolonial futures, together?6,7

Poetry is not a luxury: it is a bodymind necessity. Poetry is entangled embodiement: when our bodyminds move, in the multiplicity of ways that they do, we become poetry in action.

The sleeping patterns of fire ants are a synchronized dance: an entanglement of Self and Other into one Being, one Movement; a moment of rest between stanzas.

- Patricia Kaishian & Hasmik Djoulakian (2020). The science underground: Mycology as a queer discipline. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 6(2), 1–26. (open access ↩︎

- Audre Lorde (1977/2007). Poetry is not a luxury. In Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (pp. 36–39). Ten Speed Press. ↩︎

- Tricia Hersey (2022). Rest is resistance: A manifesto. Little, Brown Spark. ↩︎

- Deby L. Cassill, Skye Brown, Devon Swick, & George Yanev (2009). Polyphasic wake/sleep episodes in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Behavior, 22(4), 313–323. (open access ↩︎

- Deby L. Cassill, Skye Brown, Devon Swick, & George Yanev (2009). Polyphasic wake/sleep episodes in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Behavior, 22(4), 313–323. (open access ↩︎

- Sefanit Habtom & Megan Scribe (2020, June 2). To breathe together: Co-conspirators for decolonial futures. Yellowhead Institute. (open access) ↩︎

- Natasha Myers (2021, January 6). How to grow liveable worlds: Ten (not-so-easy) steps for life in the Planthroposcene. ABC Religion & Ethics. (open access) ↩︎

-

institutional ethnography and/as policy analysis

[critically]

(thinking about)

policy is critical.

how to analyze, explicate?

institutional ethnography offers one way…

toward a social onto/epistemological[1] “paradigm shift”[2]

that “keeps […] people* in view”[3]

*(and their everyday lives);

that “take[s] sides”[4]

to understand

“how”[5]

…?

[1] Janet Rankin (2017a). Conducting analysis in institutional ethnography: Analytical work prior to commencing data collection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917734484

[2] Dorothy Smith (2005), as cited in Janet Rankin (2017b), p. 3. Conducting analysis in institutional ethnography: Guidance and cautions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917734472

[3] Timothy Diamond, as cited in Janet Rankin (2017b), p. 5. Conducting analysis in institutional ethnography: Guidance and cautions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917734472

[4] Caroline Cupit, Janet Rankin, & Natalie Armstrong (2021), p. 23. Taking sides with patients using institutional ethnography. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 10(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-12-2019-0048

[5] J. L. Deveau (2009). Examining the Institutional Ethnographer’s toolkit. Socialist Studies/Études Socialistes, 4(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.18740/S4F60Z

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.